An audio version of this text is available here.

Part I: Sedimentation

I have never been one for grand theories, but my lack of imagination did little to change the fact that, on New Year’s Day of last year, the ocean had up and left the town of Seaside, Oregon. This should not be misconstrued as a lack of interest in the matter: I was concerned, really, from the moment we parked above the breakwater and looked out into the night and saw nothing, absolute, blackened nothing, waiting beyond the sand. I recalled an article about tsunamis, and thought about how it was a little risky to be touching down on an empty beach even as T. slipped down the concrete stairs, but as the minutes passed it became clear that this was not that. The water had simply gone, and seemed unlikely to return.

The darkness on the horizon gave way to sand under T.’s torchlight. Shoals rose out of the seabed and receded back into it, one after another, with no sign of the water. In the absence of the ocean, it was as if the sediments had begun to remember themselves, gathering into narrow outcrops and shallow valleys. We walked out into the night as if entering a tunnel: without laying eyes on our destination, but with great conviction that it lay dead ahead of us.

When I say the void concerned me, you should know that I did not find it distressing. It did not disturb me. Rather, it concerned me the way that a letter concerns its recipient. It addressed me. It sidled up close and told me to listen closely, because this next part is about you. We had business together, the not-ocean and I. And T., who walked out on the sand in silent agreement, must have heard it too.

*

The sand was soft and fine-grained, and we tracked it by the thousands into the Motel 6 (non-smoking room, second floor and on your left, with a view of the interstate). The woman at the front desk reminded us they did not offer a continental breakfast, and walked back and forth through the saloon doors to the office with great frequency, which sent a Glade plug-in into fits trying to punctuate each pass with a wheeze of vanilla air freshener.

“Room 204, then,” she said, “I’ll just take the rest of your names.”

“Sure,” I said, introducing us in turn.

“I mean,” she frowned, “Your first and last names.”

I spelled mine and she moved down the line, copying neatly onto her form.

“And the other one?”

I told her it was just the four of us.

“Sure, okay. I just could have sworn there was another one of you.” A pair of truckers, regulars, waved at her as they crossed the lobby, and she hurried over to see if they were going to Ruby’s Grill, which they were, and whether they would take five dollars and bring her some onion rings, which they would. S. was already spinning a yarn about how I introduced everyone like it was a debutante ball, and T. was laughing, and whatever had passed as another of us had sunk into the carpet and passed into the walls.

*

Part II: Compaction

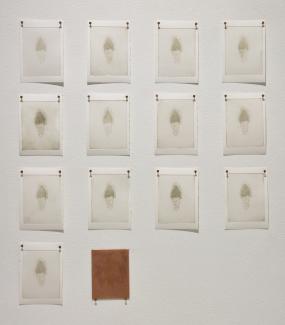

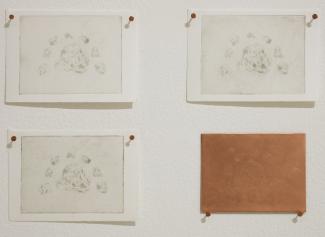

Three hundred and forty miles north, T. tells me about the tongues. She speaks in stops and starts, pulled away at intervals by a pad of paper, where she marks locations of holes and tongues in the mouth of dead water. She is surrounded by six of them, sculpted out of congealed graphite putty and errant shreds of eraser dust. They are a void, too, a not-drawing, a sacrificial pyre of gestures and dark material that was lost in order to bring an image into the world. Or perhaps a not-yet-drawing. The carbon withdraws into itself: a mass of tongues, a mass of holes. I am reminded of Leo Frobenius’s diagram of the night sea-journey,¹ which begins with one and ends with the other:

The diagram was meant to capture similarities between stories of katabasis, or underworld journeys, in early mythologies. The unifying thread, it seemed, were stories of heroes who got themselves swallowed whole by sea monsters. In the underworld-womb of the monster’s stomach, the hero comes across others who have been eaten before him, and gleans wisdom from the dead before orchestrating a grand escape. Following the trope, he will cut a hole in the sea monster’s stomach, freeing both himself and the masses. In this story, the monster’s tongue is a sentinel at the entrance to the underworld, pulling the hero down to the depths where they may receive knowledge and other transformative experiences.

It should be noted, however, that being eaten alive is not particularly hard. As an oracle warns the roman hero Aeneas: “To recall your steps and return to the world above / There is the task, and there the challenge.”² What is worth the risk of descending to the underworld, if one might never leave? For Aeneas, he is pushed forward by the loss of his father, beginning a long tradition of katabatic tales where the hero is motivated by “grief, mourning, distress, [and] fidelity unto death.”³ Perhaps organizing our stories around these ruptures, which rend our lives into a clear before and after of grief-loss, makes sense. We would give anything for a hole, a passage, a path back to before, would step willingly into the monster’s mouth as long as our loved one was waiting behind the tongue.

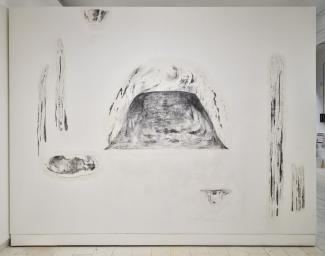

T. is tracing winding lines onto the drywall now, tall and imposing, as if she could sense the ghosts of rocky outcrops in the gypsum boards.⁴ As she works, she tells me about the river that encircles the underworld. It appears in Chinese mythology as the River of Oblivion, which souls must cross in order to be reincarnated. There is only one bridge over the river, and it is attended by an old woman, 孟婆 [maang6 po4], who offers passing souls a bowl of soup to make them forget their past lives. In Greco-Roman mythology, it’s the River Styx that the dead must cross, and the fee for a ferry ride is a copper coin, placed in the mouth of the deceased before burial. In old stories, Charon pulls the coin directly from the mouth of the deceased, while those who were buried without a coin gather on the riverbank, tongues spilling forth from empty mouths. T.’s tongues are nearly dry now. They are difficult to place, resting between these mythologies. They gather in droves, expectant, reaching, tasting. They offer strange payment, or—perhaps more unsettling—they reach out to beg for a morsel that will bring them across the river to us. These are hungry ghosts.

*

Part III: Erosion

Our group is spread unevenly over the trail to Thistle Creek Mine, clumping at the switchbacks like spoiled jam in order to make room for the regular rockfalls that tumble down the canyon. When we reach the entrance to the mine, T. offers up a lantern and we pick our way around the shallow waters in the first passage. At the first junction, T., traces a copper vein to the left, and I tie the lantern onto a borrowed hiking pole and slip to the right, following the flowing water.

After twenty metres, the tunnel drops into a flooded section of the mine, leaving only a gently rippling pool of black water at the downturn. I crouch to try and see further into the mineshaft, and am greeted with my own reflection: dark silhouette, curled over the pool, carrying a pole-and-lantern like Chiron on the river Styx. How strange, I think, that I’ve found myself far underground, dressed like the ferryman. How appropriate, I think, that it was T. who pressed the lantern into my hands. The pool of water stirs. If there are things beneath the surface, the light has disturbed them. I am tempted to reach out and touch the dead water. I wonder if I have been tricked into coming here, into guiding something forth from the dead river, into cutting a breach between our two worlds and letting the underworld pour out into ours. I make a note to ask T. about that.

*

A month passes before our paths cross again. T. is tending to her graphite pools, which she swirls and drains on two slabs of drywall (twelve feet wide, one half inch thick, thoroughly banged at the corners in the delivery truck). She is crouched over the pools like Odysseus over a pool of dark sheep’s blood, which granted the ghosts of his loved ones the power to speak with the living. T.’s pools evaporate before ghosts can gather. They dry down to holes and caves and crevasses. The image enfolds its own absence. It is dark and low like a graphite deposit, as cavernously empty as a mountainside stripped of gypsum. T. traces the edges of each pool with broken lines, as if stitching two sides of a wound. She folds the underworld up neatly, and places it to the side.

There is a stain on T.’s sweater as she packs up to leave that night. I recognize the grief-loss in the halo of graphite. It is as if we are out on the sand again, as if the edge of her sleeve found the edge of the water while she wasn’t looking. As if something reached out from the abyss to mark her, and say: we are coming back for this one.

*

Endnotes

1. L. Frobenius, Das Zeitalter des Sonnengottes, (Berlin: Reimer, 1904), 30.

2. Qtd. in The Descent of the Soul and The Archaic: Katábasis and Depth Psychology, ed. Paul Bishop, Terence Dawson, and Leslie Gardner, (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2023), ix.

3. Paul Bishop, “Is The Only Way Up?” in The Descent of the Soul and The Archaic: Katábasis and Depth Psychology (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2023), 3.

4. Gypsum, the main component of drywall, is a mineral. In other words—our walls were lifted from the earth.