As I write these words, for an exhibition that I will most likely not be able to visit, I feel uncannily familiar with the works on display, as if I had walked about the gallery space and felt the affective atmosphere dangling in the white cube. Damla Tamer’s works span continents and bridge the otherwise insurmountable physical and temporal gap between Canada and Turkey. From afar, I imagine the exhibition venue as a giant stomach, attempting to digest what we have been going through in Turkey–and most likely other parts of the world–over the last decade. An amorphous collection of undigested experiences sprouting in a garden of hope, or the garden of undigested experiences, as I would like to call it.

To me, the temporal universe of Biber Bahçesi/Pepper Garden opens up vaguely around 2015 in Turkey. It was a peculiar year, to say the least. That year, tens of violent attacks, most of which were claimed by what was later called the Islamic State, took place across the country. Simultaneously, the Turkish Army launched military operations in Kurdish towns, killing hundreds of people accused of allegedly engaging in terrorism. On July 15, 2016, a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces attempted a coup d'état, the failure of which was followed by a prolonged declared state of emergency. In retrospect, I now realize that those events laid the foundation for the construction of what some political scientists refer to as a “new” or “post fascist” regime. The continuity of this regime required a politics of shock and awe, which destroyed our senses of historical continuity in both the collective and personal sense of the word. The production and distribution of shock—whether a military attack or a spike in currency rates—became a rule of governance. By then, the vitality of the Gezi Uprising of 2013 had waned, and its eventfulness had diminished. The horizon of expectation it opened and the affective forces it unleashed, however, still lingered in the air.

Loose structures made up of transparent ropes hidden beneath a slurry of mushed papers, knots, tassels, and stitches entangled in texts all attempt to mend the broken lines of historical experience. Let us think of the act of digestion as a process of extracting what has been swallowed in such a way that it integrates previously neglected pieces together anew. It is in this sense that the works in the exhibition invite us to try and relate to the repression and violence unfolding in the artist’s faraway home. These works want us to bite them, chew on them, and swallow them—so that we come to digest the peculiar recent history of Turkey as a multitude of stories of resistance and survival rather than a single narrative of defeat.

This is perhaps why the process of creating these works is similar to that of cooking, eating, and indigestion. The Surface Conditions series, which turns the Istanbul Convention and the presidential decree announcing Turkey's withdrawal from it into a mushy slurry before spraying it over transparent, thin threads and allowing it to dry, is an attempt to digest the consequences of a presidential crime that will leave many women helpless in the face of violence against women. A few years ago, in a gathering, Meltem Ahıska used the term “undigested experience” to characterize our collective structure of feeling: “We cannot even chew on what we are going through, much less digest it as an experience,” she then explained. I recall talking briefly about how fermenting kefir kept me sane. I was fascinated by bacteria that reproduce themselves endlessly. Reproduction at its best, I thought, and what an effortless way of staying alive.

Surface Conditions possesses a captivating vitality, reminiscent of the awe-inspiring bacteria that once captivated me. It allows us to situate the lived awe within a historical continuum, while not being able to devour it completely. It makes us feel as resistant and tight as an invisible thin rope, just like the women on the streets of Turkey who keep on protesting and defending life itself.

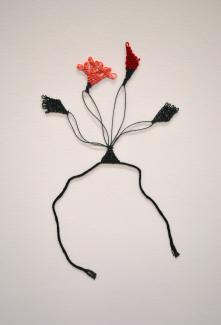

Tassels strung on thread, a piece of dyed yarn, broken threads, unraveled strands, wool, red ribbon, knotted pieces, strings woven and buried in paper, flags torn from documents, knots embedded in paper, large, seemingly directionless and irregularly stitched seam marks... What do they stitch together? Two bomb attacks, one in Ankara during a demonstration for peace and the other in the border town of Suruç where young socialists were on their way to show solidarity with Kobane, killed hundreds of people in a second of a blast. Such sheer violence was hard to swallow and impossible to stomach. Strings, threads, yarns, tassels, fabrics, and objects embedded in handmade paper in the In Lieu series speak of the unspeakable and un-understandable in a different language. This is the language of the body, which expresses itself when swallowing or gasping for breath and ultimately when it cannot digest. This language of textiles reveals how our collective capacities of perception, cognition, and narrativization had been violently crippled while we found a way of expressing them all the same.

Just like the figure of the red pepper. This is a well-known motif used in many parts of Anatolia, and from hearsay, it is known that when a woman wears a scarf ornamented with chili peppers, she gives a public signal of tension in the home without resorting to words. Red pepper also brings to mind a common saying, as in “I’ll rub chili in your mouth,” when one should refrain from saying something that is considered unspeakable or shameful. In both senses, the giant lace mountain of red pepper, or Pepper Mountain, as the title of the work has it, lingers on the shores of the speakable but brings about a certain truth. One has to go through the bitter-sweet mountain of anger, frustration, and anxiety in order to come down, perhaps not healed but transformed.

Basket Sketch for Womb (Time Moves in One Direction) is perhaps a smaller and less public “stomach” within the majestic stomach-space of the gallery. It chews on and swallows bits and pieces of a rather personal history: a bunch of dandelions and other materials such as hair, red wool, threads from the Turkish flag, and the articles of the Treaty of Lausanne on the 1923 population exchange between Turkey and Greece, which functioned to “purify” the nation at the founding moment of the state. A family’s past and its untold memories, stately symbols, and words are woven together using the cordage technique, which keeps the woven strings strongly together by creating friction between the two ends of the rope. The basket is made up of violent and compassionate memories of the past, but we do not know what is going on inside, what is being digested, or what will come out of the process of ingestion. Hope lies therein.

All works included in this exhibition deal with the recent history of Turkey—both on a personal and collective level. Yet, in these turbulent times, Biber Bahçesi/Pepper Garden inescapably speaks to what is happening in different parts of the world—from Ukraine to Gaza. On that note, the absence of works dealing with the artist’s current “hometown” Vancouver appears more telling. Access Gallery is situated within the unceded Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh territories. When there is no treaty or document to be found that proves the violence of colonial pasts and possibly the present, what is left undigested?

This is, nevertheless and fortunately, a garden—a garden where red peppers and delicate dandelions grow side by side.