In her newest body of work, Genevieve Robertson’s large-scale drawings on paper are made with pigments from found carbon-based materials—coal, charcoal, and graphite. carbon study: walking in the dark begins with the personal, and speaks to the cultural phenomenon of environmental grief. Originating from walks in the Kootenays, where coal and graphite mining are present and widespread forest fires have become increasingly destructive, this work isn’t so much about this locale as it is about locating oneself. Robertson’s practice of walking in an unfamiliar landscape, sometimes in literal darkness, other times in an atmosphere obscured by smoke, is a practice of spending time.

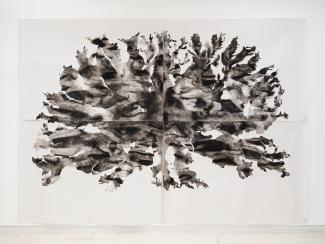

Made primarily during a residency at Access Gallery, the work exhibited in carbon study: walking in the dark, is a departure for Robertson, drawing on previous methodologies but taking bold steps in scale and abstraction. As with her bitumen and seawater based series, Language for the Wrack Zone, in this work, Robertson used scientific studies as an entry point for a material investigation. Drawing on research material of flora and fauna from the carboniferous period, the series results from what Robertson refers to as a “sustained effort to capture an elemental and lively quality embedded in these fossil and plant derived materials.” At times identifiable (a leaf, a bone) or falling entirely into abstraction, the drawings share a figure/ground relationship that reads as botanical taxonomy.

These forms arrive from research into a specific place and material, but in their reiteration become more symbolic than scientific. Robertson’s forms repeat and are distilled to an interpretation. The resultant drawings construct an intuitive language belonging both to the artist and to the geological record beneath our feet. She’s developing a vernacular of uncanny subjects that are at once animated and exhausted.

Carbon is the basis of our environment, our bodies—and what remains with its/our destruction. Robertson’s interest in the fecundity of the carboniferous period, from when much of the coal that we burn derives, is rooted in the metaphor of the material—it carries both life and decay. Similarly, charcoal in the form of wood carbonized by forest fires, is charged with the environmental precarity of our times. Interestingly, her collected graphite doesn’t feature in these drawings as much as she anticipated. If the drawings are a way of considering the life of the material itself, graphite, the naturally occurring form of crystalline carbon gave way to the carbon resulting from various life cycles. Carbon based life is always in the process of its own construction and destruction. Similarly, a drawing exists on a continuum of its own making—or unmaking—and in its own way, carries a sense of time. A drawing can always be undone. Paper itself can be returned to pulp. Marks contain the authority of the draw-er, but as much the risk of eraser.

To make the pigment, Robertson breaks her collected materials with force, and grinds them in a mortar and pestle. This powder is then mixed with a binder of honey and gum arabic to form a pigment, which she uses in various dilutions as a drawing medium. As the pooling pigments dry on the buckling paper, the various compounds arrange into strata. Particles collect around the pool’s meniscus, at times creating a dark outline, which alternately lifts and flattens the image. The reflective crystalized carbon gives the drawings dimensional qualities both real and perceived.

The drawings contain within them an atmospheric, sometimes physical structure akin to external skin, internal bone marrow, or lunar surface. Robertson’s subjects are cancerous, decaying, cracked, and dessicated; but also moist, productive, and floral. Their material enticement only adds to the drawings’ bleakness as we consume these abject and discarded organisms. It is a duality Annie Dillard witnesses as she walks her property in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1990):

I don’t know what it is about fecundity that so appalls. I suppose it is the teeming evidence that birth and growth which we value, are ubiquitous and blind, that life itself is so astonishingly cheap, that nature is as careless as it is bountiful, and that with extravagance goes a crushing waste that will one day include our own cheap lives, Henle’s loops and all. Every glistening egg is a memento mori. (Dillard, 157)

In her most confronting drawing to date, Robertson uses the lichen as a starting point, expanding it to a monumental scale. One of the oldest and most resilient organisms, lichen are a composite of cyanobacterium living among fungi, ranging from symbiotic to parasitic. On this scale, it is less a specimen to consume, than an environment that consumes us. Curious as to when (in Western thought and English specifically), we first conceived of ourselves as in the environment rather than of nature, I turned to the word’s linguistic origins. From the french environ it has always carried the sense of surrounding. Its ecological sense was first recorded in the mid-20th century, alongside the rise of conservation movements. Even as we aim to question our impact, the word we use reflects our unchangeable position and arrogant superiority.

Robertson sites multispecies feminist theorist Donna Haraway’s collection of essays Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2016) as a text resonating with her practice. In it, Haraway positions us as a solution oriented culture, but proposes instead that the first step to change is to acknowledge where we are, and to process this grief. Robertson’s collection of these materials was a way of spending time and processing a sense of environmental change (whether personal or climate). Visiting sites of mining extraction and areas decimated by forest fire—each manifestations in the landscape of capitalist violence—was a way of processing the weight of an unknown future. Robertson’s collected materials and subjects speak to a cycle and our position in an elongated geologic time. Alongside the liveliness that has so captivated her, these generative explorations hold space for the darkness and uncertainty of grief.

Katie Belcher, curator