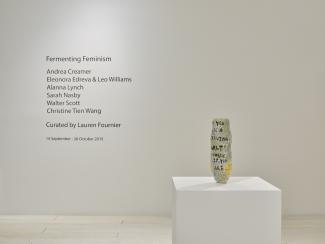

Fermenting Feminism is a site-responsive curatorial experiment led by myself in collaboration with an ever-changing, transnational community of fermenters and feminists. The conceit of the project is that fermentation, or the process of microbial transformation, becomes a material practice and speculative metaphor through which to think through pressing issues related to intersectional feminisms. The larger project has taken shape across media and forms, from exhibitions and screenings, performances and listening sessions, experimental colloquia and outreach programs, and publications. Fermenting Feminism began in 2016 as a publication made in collaboration with the Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology, and has since bubbled up in Kansas City, Copenhagen, Toronto, Montréal, and Berlin. Now, Fermenting Feminism is bubbling up on the coastal, colonized lands of Vancouver, on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. Bringing this project to Access Gallery, located where the Downtown Eastside neighbourhood meets Chinatown, introduces a richly complicated environment for fermenting feminisms on the West Coast.

Facing north on East Georgia Street, the windows to Access Gallery feature a site-specific vinyl installation—a still from Walter Scott’s XINONA. Here, what began as a web-based narrative work commissioned by the National Film Board becomes a window installation in East Vancouver. The windows of the gallery are transformed into the viewfinder of Xinona’s spaceship, with Xinona—curious and skeptical—looking through to what is going on inside. The text reads,

“Kombucha as a sticky allegory where language goes to die.”

Scott is perhaps best known for his Wendy books, a series of graphic novels that follow Wendy—a kind of beloved ‘basic bitch’ of the contemporary Canadian art world—through her many misadventures with different characters in Vancouver, Montreal, and Fogo Island. XINONA extends the universe of Wendy to the realm of sci-fi, with the Indigenous character Xinona—who we know from the Wendy series as Winona—living on her traditional, ancestral home of Kombucha planet.

Embodying hip consumption and a purportedly-progressive cultural capital and cache, kombucha (the fermented sweet tea tonic) becomes an incisive metaphor for Indigenous identity in the contemporary context of so-called Canada. As an Indigenous artist, Scott seems cognizant of the ways that Indigeneity has acquired a desirable charge in relation to both neo-colonial and anti-colonial activities during Canada’s sesquicentennial celebrations and protests. The question of the Indigenization of arts and cultural institutions—in contrast to decolonizing, which would see a full-on restructuring of the very foundations of those (colonial) institutions—continues to be contested by Indigenous scholars, artists, and critics. Scott creates a sci-fi allegory of an Indigenous “kombucha planet” to take this up in a subtly satirical way. Using the platform of a National Film Board of Canada commission that is itself branded under the Canada 150 umbrella, Walter’s XINONA is an effective intervention into the problematics of the sesquicentennial and the perhaps well-intending but ultimately fraught efforts at inclusion. “As I am summoned from obscurity by the government to represent myself (aesthetics are propaganda by other means),” Xinona thinks to herself, “suddenly I can feel the kombucha pulsing through me—I can see its amber hue running thru the veins on my hands as I type” [1]. Scott’s XINONA is a speculative world in which kombucha embodies the limit point of language—a kind of symbolic death. Kombucha stands in for that which both embodies and exceeds political and identificatory discourses—in all its spacey ooze.

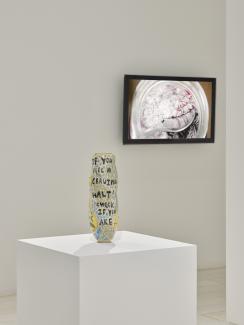

Fermentation requires vessels to hold and contain its transformative processes. In her Living Things series, Sarah Nasby works with objects designed by women throughout history and re-imagines them through fermentation. She revisits transmedial design history through functional objects like vessels and tables designed by artists like Eva Zeisel and Aino Aalto, as well as typographic fonts designed by artist Zuzana Licko (the creator of “Mrs. Eaves” font, a mid-1990s reinterpretation of “Baskerville”), literally and figuratively infusing them with the energies of fermenting matter. Juxtaposing modern and postmodern formalisms with the vibrating vitality of kombucha, Nasby invokes new ways of thinking through, and feeling about, the history of design. Sculptures hold actively changing kombucha and tea, that ferment over the course of the exhibition—the SCOBYs taking the shape of the vessels that hold them, and the sweet tea becomes sour. On the photographic prints, Nasby graphically represents fermentation’s ‘energies’ through squiggles and other semiotically-vital marks and shapes that become the background for mise-en-scenes of these female-designed vessels holding booch. Through her interventions, these objects for living become living things: vessels that we live with, and vessels animated by fermentation. Extending her experiments in graphic design, Nasby is now playing with the idea of fermenting font—where like a SCOBY, this central aspect to design becomes something fluid that can grow and change and move and take the shape of what holds it.

San Francisco-based artist Christine Tien Wang is primarily a painter, recently transitioning from painting on canvases to painting on kiln-fired ceramics that she’s sculpted by hand. Like her paintings on two-dimensional canvases, her ceramic vessels feature painted text. In the work in this exhibition, the vessel reads “HALT,” in reference to the self-help acronym that stands for

“Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired.”

Typically circulated in trauma and mental health spaces amenable to self-help and self-care, HALT is a method of checking in with oneself when one is feeling triggered or down in order to care for oneself. The logic here is that, when you are feeling one of those four things—hungry, angry, lonely, or tired—you should not make important decisions because your judgment is temporarily clouded. Instead, you ought to step back and attend to the symptom: eat, connect with someone, sleep, breathe. In her paintings, Wang often works with language alongside images often sourced from popular culture—here, emojis that signify different emotional states. Though critical of self-help books and the view of the individual as consumer or productivity machine, Wang’s replicating of the self-help acronym isn’t straightforwardly ironic. Indeed, Wang is

well-versed in body-centered ideas related to trauma (during our studio visit, we chat about EMDR [2] and The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma [3]), and she finds a sense of safety in her artistic process—especially once she gets into the flow state. Wang’s work straddles the sardonic and the sincere—with its cheekiness opening up the work for reflection on its own terms.

In Family Jewels, Eleonora Edreva and Leo Williams playfully take up ideas of queer family-making, child-rearing, and care-taking from the perspective of fermentation—where the artists feature as “parents” of their many ferments and starter cultures and vericompost. Living and working together as collaborators and lovers/partners,

Eleonora and Leo take up trans and gender non-conforming conceptions of multi-species, sustainable family structures that exist outside of reproductive sexuality. With a sense of humour, the video takes up the daily rituals of their life with their ferments like kvass and kefir, which require careful observation, scheduling, and attentive labour and love. As the artists put it,

“Parenting is an investment in the future, and ferments are the future we’re invested in. It is a future of embracing and caring for the microscopic organisms that make up our bodies and our world and folding them tenderly into our concepts of family” [4].

The artists continue to collaboratively make work related to the gut microbiome and microbial communities, grounding their work in their personal backgrounds and lives together.

Alanna Lynch’s Gut Feelings is a research-based project on the microbiome, which was exhibited in its most expanded form when Lynch received the Berlin Art Prize in 2018. The work features sculptural objects such as gloves made from dehydrated kombucha SCOBYs—a bacterial cellulose “fabric.” The gloves, which are typically meant to protect a human wearer from a contaminating agent or material, are themselves composed of the contaminating material—in this way, they come to symbolize a cross-species, “contamination as collaboration” [5] ethos of feminist fermentation. The co-mingling of contamination and protection reflects the blurred lines of mind and body, gut and bacteria, self and other, human and non-human, of the microbiome and its intermeshing of borders and bounds. Lynch is energized by the idea, now echoed in science discourse, that “symbiosis is not mutually beneficial” [6] (notably: in biology, the term “symbiosis” has recently been redefined to reflect the often disproportionate dynamics in symbiotic relationships). Alongside the sculptural gloves is a salon-style hanging of Lynch’s drawings and sketches, photographs, and written reflections on “abnormal” SCOBY growth based on her observations of her many SCOBYs in the studio. A variety of different fungi and moulds—other microbes which coexist in strange ways with Lynch’s kombucha—grow on the surface of the booch, on display in this wall-based installation that provides a glimpse into the artist’s experiments in her studio-cum-laboratory.

Andrea Creamer’s newest body of work Nothing More to Eat brings together the artist’s longstanding interest in the relationship between bread and revolution. Looking back to the French revolution (1788-89), as well as the Bread and Roses strike (1912), and the historical ties between bread, boules, and bricks, Creamer has created a series of sculptures that embody histories (and presents) of protest. In Creamer’s new installation for Access Gallery, the sourdough bread boule becomes, symbolically and then, literally, a brick. One imagines picking up the hard boule and, as if it were a brick, throwing it through a plate glass window. Creamer has cast the boules in plaster using iron oxide in the ruddy shade of Rosedale Brick—a colour specific to the artist’s current home of Toronto, Ontario/Eastern Canada, where bricks are used more often than wood. Creamer’s work as a contemporary artist as well as a social worker and community arts organizer continues to shape her practice. She was one of the early members of the Toast Collective (founded in 2008), an alternative arts organization in East Van: The Toast began as a cafe to “offer lots of breads and different spreads” [7] and evolved into an artist-run hub for imagining and realizing alternative approaches to community organizing and arts programming in Vancouver. Alongside Creamer’s longstanding interest in the history of union-organizing and protest more broadly is, specifically, the erasure of women’s bodies and the role that women play in protests. At the heart of this work is a fervent politic of class: as philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau put it in during the height of the French Revolution, “when the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich”!

The artists in the exhibition work through issues like consumption and appropriation, wellness and health, harm reduction and intoxication cultures, settler-colonialisms and decolonial possibilities, care-taking and queer family-making, inter-species symbiosis, labour and accessibility, and feminist histories of science, revolution, protest, and design. Sour and effervescent, ambivalent and refreshing, multi-sensorial and potentially explosive, Fermenting Feminism taps into the fizzy currents in critical and creative feminist practices today.

Lauren Fournier, curator

NOTES

[1] Scott, Walter. XINONA. National Film Board of Canada, 2017.

[2] EMDR stands for eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, a form of psychotherapy often used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder and related anxiety; in it, the therapist guides the patient’s eye movements from side to side, as a way of working through traumatic memories. It is seen as a nontraditional and somewhat controversial method, as some clinicians say the evidence behind EMDR’s effectiveness is unclear.

“Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy.” Psychology Today. 2017.

www.psychologytoday.com/ca/therapy-types/eye-movement-desensitization-and-reprocessing-therapy (accessed 6 September 2019).

[3] van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books, 2014.

[4] Edreva, Eleonora and Leo Williams. Artist statement, 2018.

[5] Tsing, Anna. Mushroom at the End of the World, Princeton UP, 2015.

[6] Lynch, Alanna. Studio visit/conversation with curator, 2019.

[7] Creamer, Andrea. Studio visit/conversation with curator, 2019.