NOW, NEVER

Rawan Hassan, Alex Gibson, Sidi Chen, Holding Ground

Curated by Kitt Peacock

7 November – 14 December 2024

The NOW, NEVER residency ran for one month and one day, beginning on the last legs of one crescent moon and ending as the final threads of the next disappeared from the night sky.

Five artists occupied the gallery for a full lunar cycle, working in an urgent temporal mode, seeking moments of rupture through their respective practices. Still, as I write this, it is exactly as dark as the first day they arrived. It is as if no time has passed—a familiar sense of suspension for those of us who live in troubled times.

There are several wards against troubled times, which can be dusted off and whenever the trouble threatens to disrupt capital and normative uses of time. One of the most habitual ways to ensure trouble does not not overstay its welcome is by providing a clear end date. It’s always darkest before the dawn. You’ll feel better in the morning. Ceasefire talks nearing resolution. And so on. As Walter Benjamin writes, “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule.” In other words, we are promised a crisis with an end, but it is a technology of oppression more often than it is a truth. The day that the artists arrived is exactly as dark as the day I write this.

Writing to you from the long crisis, I have a hopeless task: to write about urgent artistic practices before the dust has settled. To place works neatly into relational networks that have only just begun to form around them. To historicize them. Benjamin talked about history as a great angel whose face is “turned towards the past,” dragged by its wings into a future it cannot see. We can assume that the angel of history didn’t have much in the way of peripheral vision. How can we speak about the present, then? Abandoning the historical mode, I am left searching for a new perspective to write from.

Prison abolitionist M Gnanaisihamany once joked that each audience they spoke to asked the same question upon hearing about their work. “How do you take care of yourself,” they asked, which was really code for: “how do you not despair.” And their answer, of course, was that they did despair. And then they worked. And sometimes they despaired while they worked. In searching for a position that speaks to the atmosphere of violence produced in a colonial and carceral state, I am convinced that the only appropriate curatorial position combines these two options—the peripheral glimpse of the angel of history, and the official, embodied position of despair: lying on the floor.

I

There is a blue smudge underfoot. It is probably powdery marking paint, from earlier in the week, or else a fine sediment of chalk pastel, drifting off of Rawan Hassan’s Charcoal Rubbings of Galilean Amulets, which seems more likely given the depth of the electric blue. It has settled into the architecture of the space, and will remain in the cracks of the floor as a trace of the vellum, which passed above it half-supported by air, like a shroud suspended. A trace is an indexical sign, in that it always points back to something. A foot for every footprint. But a blue dust enfolds a thousand referents—blue as a talisman for protection, blue like an ID card, blue like the sea of Galilee.

II

There is a great privilege in being on the floor, because it is a first-hand archive of all things the beetles and worms will decompose in short order. A tuft of bison hair, a fallen rose hip (rolled behind the desk, likely kicked underneath the cabinet by now). Ecological theorist Macarena Gomez-Barris once proposed that resistance to colonial and capitalist structures must begin—quite literally—on the ground, by aligning our perspectives to those of the fish and frogs whose lives are forfeit under extractive modes. There are beings that teach us to resist through abundance—fireweed, mint, and kinnikinnick, which spill over the beds of the Healing Garden on the 100 block of Hastings Street and lend their internal chemistry to each image of Eco-Processing (2024). When they are exhausted, they return to the care of the compost heap, and are tended to by their relations—the worm, the beetle—in turn.

III

This was a place of abundance. Last month, the downpour in the gallery reminded us that this is Skwachàys, a salt marsh, as all the water falling in the city rushed to return to this place. Sidi turned a worktable around as if to confer with the growing puddle on the gallery floor. This was once a favourite resting place of teals and pintail ducks, who would stop on long migrations to dive after aquatic life in the shallow water. A month passes and Sidi is here on the rainiest days, needle moving like a pintail: above the surface, below. A pile of mended garments rest here, starched and waiting, for sunlight to dry benches and concrete medians before they disperse. This was a place of abundance.

IV

Join me with your back to the pillar—perhaps we can claw our way up from here. There was an early experiment on human vision, which determined that light hits our retinas upside-down, and our brains are in the habit of flipping the image as we perceive it. In other words, one can only stand up because we are in the habit of orienting ourselves that way. Queer theorist Sara Ahmed speculated on this habitual orientation, writing: “If this involvement is seriously weakened, the body collapses, and becomes once more an object.” Call it a swoon, call it a fall, we are brought into a queer condition of collapse, where the body is at odds with the world.

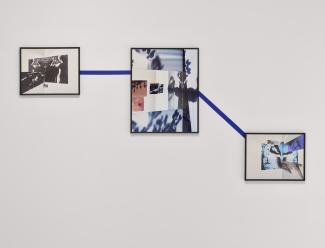

There’s a body collapsed around the column of Image bars (116 in), somewhere between sexy and desperate for stable ground. It crawls and drags down the screen—or up the screen, if I am orienting myself to this new collapse. Light, at least, has a practical approach to orientation, in that it will dead reckon its way from one object to the next. It is exacting, like a cigarette burn in a carpet, or the sharp edge of a mirror, or the flash and scrape of a scan-head camera. Sara Ahmed, again: “some bodies more than others have their involvement in the world called into crisis.” The light is a simple orienteer: it touches you, it places you in this world.

Alex Gibson (b. 1994) is a Barbadian born, queer artist based on the unceded traditional territor0ies of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, colonially known as Vancouver. As a non-binary artist, they are interested in queer identity, space, and temporality, where they filter digital and material processes to generate imagery, and archive ephemera through image making, video, and installation. Gibson’s work has been exhibited at Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Como, Italy; Capture Photography Festival, Vancouver; Wil Aballe Art Projects Vancouver; Tomato Mouse, New York; Artists Alliance, Bridgetown, Barbados. They hold an MFA from the University of British Columbia.

Rawan Hassan is an interdisciplinary visual artist based on the unceded and unsurrendered land of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. Her works explored the complex relationship between preserving and evolving Palestinian textile traditions, such as tatreez (embroidery). She does so through studying and making said traditions through a diasporic lens. She also simultaneously explores materials that embody the questions of what was and what could possibly be with the textile work. Her hope is that her practice might open up the conversation on Palestinian identity, grief, resilience, resistance against erasure, ongoing occupation and colonization.

Holding Ground is a collaborative project of Cait Gentle and Sarah Comyn - emerging from the compost pile of Hives for Humanity (2012 - 2024), a community-serving non-profit which they grew alongside the Healing Garden at 117 East Hastings Street. Earlier this year, they made a commitment to: work within their body-limits in organizing; to resist burn-out and feel the fullness of griefjoy as an antidote and accountability to ever-present influences of settler colonialism and white supremacy; to eat with the ecosystem; to use the medicines we carry, and to release, compost, and decompose that which is no longer of use; to practice ways of being in relationships, and to resist extractive and transactional models of being.

Sidi Chen (MFA) is a diasporic queer artist who works in relational aesthetics through performance, media arts, and other interdisciplinary practices. Through their research across arts, natural science, and community development, Chen imagines alternative relations and perspectives with the world through mediations of bodily mobility and empathy. Sidi Chen is currently living and working as a practicing artist and an independent arts administrator in historical Chinatown, on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations territories, Vancouver, BC, and the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Sníchim speaking peoples’ territories, known as Burnaby, BC.

*

With gratitude as guests, Access is located on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

*

Access gratefully acknowledges the ongoing support of the following funders as well as our committed family of donors, members, and volunteers, for enabling this organization to remain vigorous and connected to the communities we support.