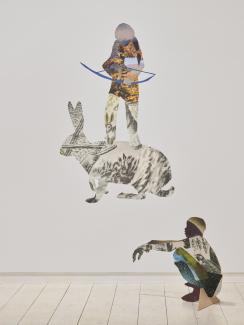

In Wanderings, Anna Binta Diallo presents an installation of photographic collages in both two-and three-dimensions. The works consider how folk stories influence the formation of identity. Iterative in nature, the ongoing installation-based project shifts with each presentation, sometimes expanding into the exhibition space through sculpture.

Of her work, Diallo writes, “Casting a wide net on our Collective History, I reinterpreted folk stories and reimagined or reused them in my own way to create new mythologies. Using archives, books, found imagery, the Internet, memory, and oral traditions, I created a series of new images that can be continuously re-organized.” Figures and animal forms, constructed from varied sources, are scattered throughout the visual field. The figures are at once historical characters and deep space wanderers, their faces made of galaxies and landforms, wearing motifs “built from the textures, debris and remnants of various cultural inheritances. They wear the rich patterns of forests, black-and-white ethnographic drawings and vibrant purple fabric—infinitely alterable assemblages of what was and what is to come.”[i]

If photography freezes a moment in time, these collaged images release and recapture this moment, turning photographic fact towards expansive folklore. Diallo’s images reject a single truth, implicating myriad understandings of Self and Other. Drawing on a wide array of stories and perspectives, Diallo reveals the affinities and tensions that exist between these and the mythologies of her own Franco-Métis and Senegalese ancestry, striving to make work that questions and subverts patriarchal ideals and racism. Easing her subjects from their sometimes-heavy contexts allows them to be read simultaneously as specific and unfixed. As a whole, her project engages with Othering, the legacies of colonialism and slavery, language, and contemporary issues of migration/displacement, as well as the problematic definition of geographical borders, ultimately investigating identity as it relates to various histories, loss, nostalgia, and diaspora. Through cutting, pasting, and splicing photographs, Diallo builds new fictions.

Visual media—by nature immediate and ahistorical—is uniquely suited to “restore the nonsequential energy of lived historical memory and subjectivity” as fundamental to the construction of meaning.[ii] Diallo plays with the potential of collage to conflate time or re-remember the past, but through its iterative nature and disruption of visual space, she resists linear definition. The evidently fabricated nature of collage belies any attempt at deception—even digital collages have seams.[iii]

“As the early twentieth century discovered the power of images and photography, artists felt the urge to reconfigure this amorphous mass of anomic images by creating connections, links, possible narrative, sudden classes, and interpretation. It was an attempt to make sense of the world, to structure it, while still reserving its absurdly cacophonic, at times sublime, multiplicity.

Since its very origin, collage has appeared as an art of crisis that has entertained a deep relationship with traumas and violations.”[iv]

We are taught that literature and visual art are imaginative and constructed, but science and history are immovable. Yet, evidenced within living memory, we know that facts—planetoids, espionage files, dietary advice, national borders, dinosaur species, etc.—are elastic. Our attachment to geography as static, “the idea that space ‘just is,’ and that space and place are merely containers for human complexities and social relations, is terribly seductive: that which ‘just is’ not only anchors our selfhood and feet to the ground, it seemingly calibrates and normalizes where, and therefore who, we are.”[v] Writer Taiye Selasi speaks of holding space for multiple experiences in a world bent on categorization,

“… to say that I came from a country suggested that the country was an absolute, some fixed point in place in time, a constant thing … In my lifetime, countries had disappeared—Czechoslovakia; appeared—Timor-Leste; failed—Somalia... To me, a country—this thing that could be born, die, expand, contract—hardly seemed the basis for understanding a human being.”[vi]

Ultimately, Selasi proposes replacing the question where are you from? with the more nuanced where are you a local? in an attempt to find echoes in our experiences. Despite varied nationalities, we may share numerous localities that inform how we host, give, avoid, navigate, etc.

Diallo’s work upends a sense of linear time privileged by official curriculums that “conceal colonialism’s processes of self-invention, a history marked by white supremacy’s erasure and rewriting.”[vii] In Demonic Grounds, Katherine McKittrick speaks to the knife’s edge of locating these erasures while resisting the replication of white/colonial history-making. “I have turned to geography and black geographic subjects not to provide a corrective story, nor to ‘find’ and ‘discover’ lost geographies. Rather, I want to suggest that space and place give black lives meaning in a world that has, for the most part, incorrectly deemed black populations and their attendant geographies as ‘ungeographic’ and/or philosophically undeveloped.”[viii]

The imagery refuses a fixed truth or identity, attending instead to the cultural efflorescence or resonances emerging from multiple stories.[ix] In her work, I see a distinction between fact, which as Toni Morrison describes in The Site of Memory, “can exist without human intelligence,” and truth, which cannot.[x] Like Morrison, reconstructing interior black lives through investigating their remains, as opposed to their monuments, Diallo builds her visual fictions from the inner and outer worlds of her subjects. References to West African villages, colonial era military personnel, Indigenous hunters, suited men, text in several languages, hoop skirts, and the cosmos, explode a linear chronicle. Of Black archival practices, Maandeeq Mohamed writes, “We know that the archive will never be sufficient – if we are accounted for, it is via the violence of fact: scientific racism, and catalogues listing enslaved people as property. … Perhaps not knowing can be useful, insofar as it allows for a recognition of the fact that what is/isn’t archived is but one of many fictions (a dominant one to be sure, but still fiction nonetheless) that constitute blackness in public life.”[xi]

Refusing to privilege any fact over folklore, Diallo makes space for complex and contradictory experiences. Diallo’s figurative images, collaged from visual material such as magazines, scientific and historical illustrations, literature, and personal archives, are grouped in unexpected arrangements, and extend into the exhibition space through planar sculpture. Through shifts in scale, and use of a spatial field rather than ground, landscape conventions are disrupted as often as they are employed. As viewers, walking amongst the installation, we are implicated as participants. Animated by their interactions with each other and the viewer, these figures inhabit deep time and space. Like Diallo’s flat outline of a face containing star systems, our bodies hold collections of our own experiences, further expanding a shared narrative.

Katie Belcher, curator

This exhibition is part of the 2020 Capture Photography Festival Selected Exhibition Program. This text is published as Like all else, wandering in Capture Magazine 2020

NOTES

[i] Joy Xiang, “Bending the Light. A national survey of 10 artists who are reforming material practice,” Canadian Art, December 12, 2019, http://canadianart.ca/features/bending-the-light/.

[ii] Edward Said, “Opponents, Audiences, Constituencies, and Community,” in Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, eds. Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 1057.

[iii] Laura Hoptman, “Collage Now: The Seamier Side,” in Collage: The Unmonumental Picture (New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 11.

[iv] Massimiliano Gioni, “It’s Not the Glue that Makes the Collage,” in Collage: The Unmonumental Picture (New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 2007), 11-12.

[v] Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xi.

[vi] Taiye Selasi, “Don’t ask where I’m from, ask where I’m a local,” Ted Talks, TEDGlobal 2014, video, 16:04, https://www.ted.com/talks/taiye_selasi_don_t_ask_where_i_m_from_ask_whe….

[vii] [1] Yaniya Lee, “Anxious Territory: The Politics of Neutral Citizenship in Canadian Art Criticism,” C Magazine 128 (Winter 2016), http://cmagazine.com/issues/128/anxious-territory-the-politics-of-neutral-citizenship-in-canadia

[viii] McKittrick, xii-xii.

[ix] Here I’m borrowing the term from Hoptman, “Collage Now: The Seamier Side,” 11.

[x] Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2d ed., ed. William Zinsser (Boston; New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), 93-94.

[xi] Maandeeq Mohamed, “Somehow I Found You: On Black Archival Practices,” C Magazine 137 (Spring 2018), http://cmagazine.com/issues/137/somehow-i-found-you-on-black-archival-p….