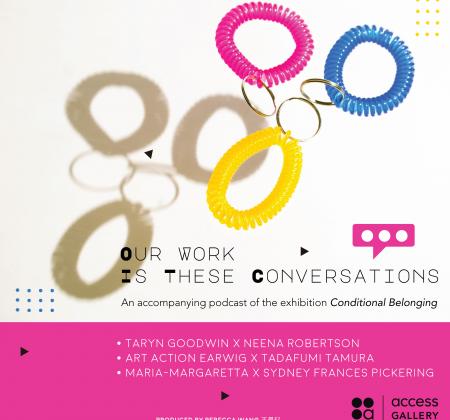

Bringing together local emerging artists with distinct backgrounds, Conditional Belonging makes space for their nuanced personal/communal narratives around power relations, access, resistance, and healing through a variety of mediums such as shadow puppetry performance, beadwork, video, and photography.

By using materials and techniques available at hand, Art Action Earwig, Taryn Goodwin, Maria-Margaretta, Sydney Frances Pickering, Neena Robertson, and Tadafumi Tamura complicate the discourses around “normative” ways of being and the “standard” value system in a settler-colonial context.

By recontextualizing memories, events, and fiction across time and space, and through kinship and location, Art Action Earwig and Pickering transform personal narratives into sites of collective healing. When faced with disempowering policies, Goodwin and Robertson confront power-laden colonial frameworks with creative interventions to validate their presence and occupy public and institutional space. Through activating the nuances and symbolism embedded in everyday objects, Maria-Margaretta and Tamura communicate the intangible and relational value accrued from embodied knowledge.

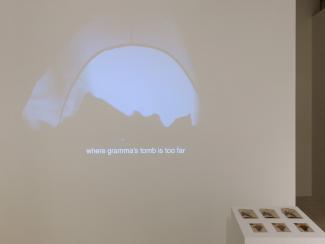

With a tent transformed at once into a rally spot, a city square, a forest, a tomb, and a womb, Art Action Earwig’s shadow puppetry performance and zine, Home Squat Home, weaves together personal, factual, and fictional vignettes that reflect on environmental justice, labour, migration, housing security, kinship, gender, and death.[i] An intergenerational dialogue is unveiled through alternating scenes between the collective’s two homes of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and Seoul, Korea. Desire for true care and hope brought by grassroots movements such as the Women’s Memorial March in honouring missing and murdered Indigenous women and actions of solidarity among tent city residents in Strathcona Park are illustrated throughout the piece.[ii] With a dreamlike soundtrack and soft singing by collective members Minah Lee and Wryly Andherson, the audience is transported into a world where a childhood lullaby is capable of time travel and connecting us back to nature.

For Lil’wat artist Sydney Frances Pickering, the bodies and stories of her community are interconnected with those of the sacred water and land of which they have been caretakers since time immemorial[iii]. In her multi-media installation Unceded, beadwork, driftwood, poetry, video, and manipulated found photography come together to tell a story of land grabbing, resource extraction, and Indigenous resilience. Rupturing the Western linear timeframe by merging the past, present, and future, Unceded attests to the unwavering presence of Pickering’s people, both literally (on the land and water) and metaphorically (on the map). The innate connection between the Lil’wat people and their territory conveyed in the piece suggests that permanent colonial settlement is itself an unrealistic fiction.[iv]

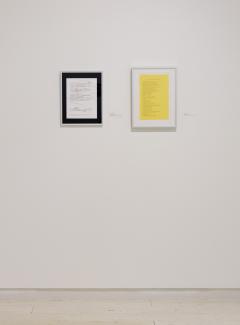

The same spirit of defying authorities and (forced) resourcefulness from Unceded is present in artist and community organizer Taryn Goodwin’s work. A self-care list and collaged accessibility service application, Manifesto and Ideal School Project are testaments to Goodwin’s determination to shape their own reality and inspire change in their community, as well as their continued effort in championing lived experiences over hierarchical institutional frameworks. Considered by Goodwin to be “cultural activism,”[v] her work is a reminder of how simple gestures can be radical and effective in advocating for “self-defining sustainable practices” that honours one’s own pacing and Bodies of Knowledge.[vi]

In the fast-paced contemporary world, almost every move one makes seems to be at odds with the natural ways of being. When did the interests of man-kind and nature become a dichotomy, given that our original embodied knowledge comes from nature which was once our only fertile playground? In her photography series, Hide and Seek, photographer Neena Robertson, makes visible the often obscured “power dynamics between humanity and nature as well as their physical parallels” such as decay and regeneration.[vii] Created at a former camping site of unhoused residents on the unceded and unsurrendered traditional territory of the lək̓ʷəŋən peoples on the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations (otherwise known as Victoria BC), the series sheds light on uneven access to land, and the resulting displacement and persisting stigma around people experiencing homelessness.[viii]

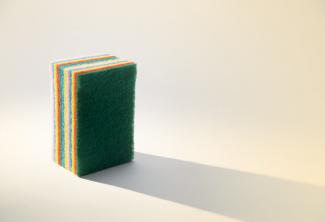

Displacement and the Asian diaspora are among the themes that first generation Japanese immigrant and photographer Tadafumi Tamura has explored in his practice since moving to Vancouver eight years ago. While dedicating part of his practice to capturing moments of solidarity and empathy in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, he refers to his still-life series Plastic World as a self-portrait.[ix] Tamura photographs meticulously staged, low-cost household items, with which he would spend hours while working at a dollar store owned by a Korean immigrant family.[x] Not only does Tamura comment on the undervalued labour involved in mass-produced goods, the negative connotation of plastic products on which our lives are heavily reliant, he also wants to bring attention to the invisible hardships endured by immigrant families to build their lives abroad. Furthermore, Tamura draws negative parallels between the stereotypes imposed on these largely “made in China” items and victims of anti-Asian hate crimes—all the more poignant given the surging anti-Asian racism since the beginning of the pandemic.[xi]

Also taking mundane objects as the subjects of her work is Red River Métis artist Maria-Margaretta from Treaty 6. In her practice, Maria-Margaretta employs strategies such as humour, subtlety, and refusal to (re)negotiate how her personal and familial stories are archived in a colonial system where cultural hybridity is ubiquitous.[xii] With titles such as Go Help Grandma With The Dishes, Look Under The Sink, and One Day I’ll Have A Blue Room Again, each work provides just enough context to tap into the public’s collective memory without revealing too much of the personal narratives attached to them. In an accompanying performance of Go Help Grandma With The Dishes—a pair of beaded rubber gloves—she activates and adds meaning to the piece by using them in everyday activities such as washing dishes—specifically English teaware. In these works, Maria-Margaretta “utilizes domestic spaces and objects of home as a way to speak to cultural knowledge and stories through the incorporation of materials and Métis kitchen table methodology.”[xiii]

Beginning with the question “what does it mean to make art with limited access and capacity?”, the making of this exhibition has evolved into an investigation of how multi-faceted limited access and/or capacity could look like for artists in intersectional positions.

Working within their varied realities and cultural contexts, these artists tell their stories of alternative ways of being, knowing, and making outside the parameters set by the hegemonic ideologies that centre power and privilege. In their works, boundaries between art and craft, traditional and contemporary art, and established norms and lived experiences are blurred. Structural barriers, whether access, economic, linguistic, or cultural, become catalysts for art-making, where underrepresented voices find space within and beyond the dominant cultural structure. Filled with both vulnerability and resilience, these works allow the audience to enter the narratives tethered to them through conscious and reflexive artistic choices made by the artists. While the phrase “conditional belonging” often refers to how the minorities or new members of a community have to conceal or refrain their true attributes and conform to set standards in order to fit in;[xiv] this exhibition exposes the harm and struggle induced by this liminal state, celebrates the resilience and resourcefulness of those who champion their own nuanced perspectives, therefore makes possible moments of true belonging and (collective) healing.

[i] Art Action Earwig, “Home Squat Home,” Art Action Earwig, 2020, https://www.earwig.space/home-squat-home/.

[ii] Art Action Earwig, “Home Squat Home,” Art Action Earwig, 2020, https://www.earwig.space/home-squat-home/.

[iii] Conversation with the artist, May 9, 2021.

[iv] Sydney Frances Pickering, “Unceded,” Sydney Frances Pickering, https://www.sydfrances.com/unceded.

[v] Taryn Goodwin, interview by Michelle Cyca, “Taryn Goodwin Is Building a Community of Disabled and Neurodivergent Artists,” Emily Carr University of Art + Design, March 12, 2021, https://www.ecuad.ca/news/2021/taryn-goodwin-is-building-a-community-of-disabled-and-neurodivergent-artists.

[vi] Taryn Goodwin, “What’s In A Word ‘Access’,” self-directed study at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, spring 2021, 5.

[vii] Neena Robertson, artist’s statement of Hide and Seek, 2021.

[viii] Neena Robertson, artist’s statement of Hide and Seek, 2021.

[ix] Conversation with the artist, March 13, 2021.

[x] Conversation with the artist, March 13, 2021.

[xi] Tadafumi Tamura, artist’s statement of Plastic World, 2020.

[xii] Conversation with the artist, May 21, 2021.

[xiii] Conversation with the artist, July 22, 2021.

[xiv] Neta Yodovich, “Defining Conditional Belonging: The Case of Female Science Fiction Fans,” Sociology, October 31, 2020, 7-8, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038520949848.